Where is the defense for the constitutional order from our federal leaders?

Last week this newsletter argued that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's aversion to any and all matters related to the Constitution indirectly set the conditions which may have contributed to the current strain to the constitutional order. The ramifications of this federal passivity revealed itself once again, this time with Ontario Premier Doug Ford's Progressive Conservative government passing of Bill 28 last Thursday.

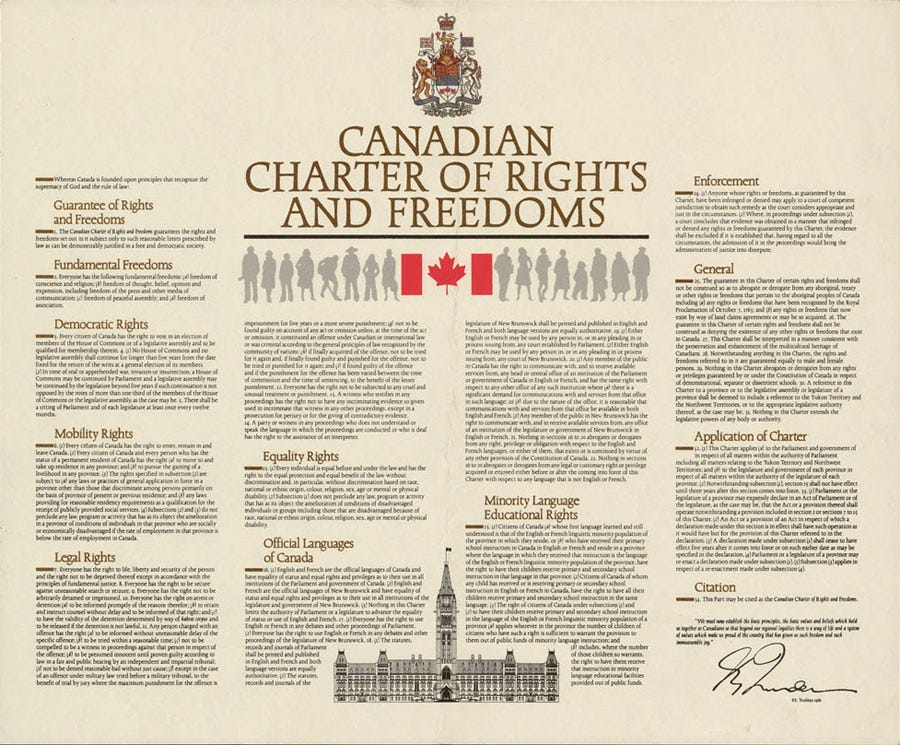

Bill 28 pre-emptively uses the notwithstanding clause, Section 33 of the Constitution Act 1982, to override labour rights by banning strike action and imposing a contract on the Canadian Union of Public Employees' (CUPE) 55,000 education workers, well before a strike was even in effect, or collective bargaining had reached a natural end point.

Throughout the 40 year history of the notwithstanding clause - a measure initially designed as a check on judicial activism by permitting provincial legislatures to override certain Charter protections enforced by the courts in pursuit of implementing its own laws - never has it been used in the context of a labour relations dispute, and so Ford's use of the constitutional provision in this manner is the single biggest threat seen to the labour movement and for the future of collective bargaining.

Despite the widespread consternation with the application of Section 33, it is important to observe that the notwithstanding clause is a perfectly legal instrument, and its inclusion was part of the grand compromise Pierre Elliott Trudeau had to agree to with the provinces in order to repatriate the Canadian Constitution, while enshrining with it a Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In other words, Canada would not have the Charter in the first place, if not for the existence of its notwithstanding clause.

The quick and unanticipated popularity of the Charter, along with a growing distrust of politicians in general, made the notwithstanding clause a politically toxic proposition for any level of government considering its usage, for fear the public would toss them out for overriding their fundamental Charter rights.

However, the current crop of federal leaders, chief amongst them being Trudeau himself, transformed the perception of constitutional overrides from the provinces as a more palatable exercise, witnessed primarily when Quebec Premier Francois Legault used the clause with impunity for both Bills 21 and 96, limiting religious and linguistic rights respectively, while also purporting to unilaterally amend the Constitution to affirm Quebec's nationhood, which most constitutional scholars had deemed to be an unconstitutional manoeuvre. Nonetheless, Trudeau permitted the unconstitutional initiative from Quebec, which stands in stark contrast to his current response to Ontario's Bill 28.

Trudeau's latest remarks about Ford’s usage of the notwithstanding clause had the pretense of condemnation, but by unpacking some of his statements, it gives way to other troubling impressions:

“Canadians should be extremely worried about the increased commonality of provincial governments using the notwithstanding clause pre-emptively.”

An astoundingly ignorant comment, this “increased commonality” has developed solely during his tenure as Prime Minister, without any stern challenge on his end, either legally or even rhetorically, in all prior instances of its usage under his watch. Any seeming normalization of the pre-emptive use of the notwithstanding clause would have begun with Trudeau's acquiescence to Quebec's Bill 21 & Bill 96, as his complicity towards the nullifying of religious and linguistic minority rights respectively set the table for Ford to now do the same to labour rights, essentially daring Trudeau to respond in hypocritical fashion.

“Yes, this is the federal government that stands up for people's rights and freedoms and we are absolutely looking at all different options.

It would be much better if instead of the federal government having to weigh in and say ‘You really shouldn't do this, provincial governments,’ it should be Canadians saying, ‘Hold on a minute. You're suspending my right to collective bargaining? You're suspending fundamental rights and freedoms that are afforded to us in the Charter?’”

What would the Prime Minister suppose the citizenry do to stand up to this constitutional assault? The average citizen would not likely have the means and resources to access legal recourse to eventually take this to the Supreme Court where it needs to be settled; and, the next provincial election in Ontario is years away. Simply put, Trudeau's suggestion reveals his meekness wrapped in feigned indignation.

Yet, Trudeau has not been the only federal leader woefully inadequate in handling this matter. Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has been shamefully silent on this issue altogether. For all that has been made about the fresh Conservative electoral approach to courting working class and trade union voters, this apparent apathy to the erosion of collective bargaining rights should serve as a warning signal to those groups that may have prematurely bought into the Conservative Party's attempted billing as being labour-friendly, while also reminding workers from both public and private sector unions of Prime Minister Stephen Harper's own antagonistic approach to labour relations, the last time Conservatives were in power.

As for the New Democratic Party (NDP), since the passage of Ford’s Bill 28, the party has called for both a judicial reference to the Supreme Court to challenge the bill's legality, while also calling on parliamentarians to have an emergency debate in the House of Commons about the implications of Ford's actions. While such a response would normally be welcomed, it also leaves one wondering where all of this disaffection was from the NDP when Legault was trampling on religious and linguistic rights. It is plainly obvious that irrespective of the federal party, political expediency rules the day when it comes to Quebec.

No greater illustration of this federal cowardice was seen than in the opposition motion tabled by the Bloc Quebecois following Legault's Bill 96, which effectively articulated that Quebec had the right to assert its nationhood through constitutional amendment, and it passed 281-2, inclusive of all major federal party leaders voting in favour.

Given amending the Constitution in the way Bill 96 proposes would not fall under Section 45 as the motion claims, the easy passage in the House nevertheless can be construed as tacit approval for Legault's efforts towards his “Sovereignty-Association” project.

In fairness, beyond a possible reference case to the Supreme Court; and even the success of that endeavour is very much in question, there is likely very little the federal government can do now at this point. Several pundits have opined on the use of the disallowance clause of the Constitution (BNA Act, Section 56), which permits the federal government to effectively annul or 'disallow' provincial laws, but while these powers were used quite extensively in the formative years after Confederation, by the mid-twentieth century it became politically taboo to do so, and such a response now would utterly destroy federal-provincial relations.

Aside from the brief window presented by former Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard in amending the Constitution, any present consideration of removing the notwithstanding clause through an amendment would be nothing but a pipedream. Firstly, in order to amend the Canadian Constitution, it requires the consent of seven provinces equalling 50 per cent of the population, along with the federal Parliament (our amending formula).

If that was not difficult enough, pre-eminent constitutional scholar Peter H. Russell also reminds us of Prime Minister Jean Chretien's Constitutional Amendments Act of 1996, which indirectly gives Quebec a constitutional veto by “superimposing five regional vetoes on the operation of the 7/50 amendment rule,” meaning structural changes must have the support of British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, two Prairie provinces and two Atlantic provinces, both equaling 50 per cent per region, all amounting to closer to 92 per cent of the entire Canadian population required for major constitutional changes (Constitutional Odyssey, pg. 239).

With both Quebec and Ontario as the principal orchestrators of the current constitutional quagmire, it is clear from the parameters of the amending formula that any changes to our Constitution would be nearly impossible, thereby putting the country in constitutional gridlock, and possibly a national unity crisis. Unfortunately, if only a reference case had been put to the Supreme Court very early in Trudeau's tenure to show his willingness to defend the Constitution, it may have given pause to all that has since followed.

And so, if the continued fraying of our constitutional order is only now starting to alarm our federal leaders, they only have themselves to blame for normalizing such behaviour by not defending the cherished values that have been codified in our Constitution when they had the chance.